- Home

- Traveller guides

- The 10 oldest pubs in Dublin

The 10 oldest pubs in Dublin

The Dublin pub is a citywide institution. The best are revered and spoken about in exalted terms. They are also old – old enough to have seen and heard a few things.

With age comes experience, and the city’s oldest pubs have witnessed much of the city's social and cultural history. They were the favourite haunts of writers, politicians and plotters: many a scheme has been hatched and many a fine line has been written at the bar, or in the snug, or at a small table in the back.

Here's a glimpse at Dublin history, through the stories of its oldest pubs.

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

The Brazen Head

Neatly nestled on Liffeyside Bridge Street, the Brazen Head is Dublin’s oldest pub. There’s been a hostelry on the site since 1198, even if the building you visit today was established as a coaching inn in 1754. By the end of that century, its warren of rooms had become a revolutionary hub: local resident Oliver Bond and his fellow United Irishmen met here to plot their (thwarted) rebellion in 1798, while five years later Robert Emmet also used the bar to plan his (also failed) uprising of 1803. Until the 1960s, visitors could view Emmet’s desk, positioned as he had it overlooking the pub’s entrance to spy enemies arriving from nearby Dublin Castle.

Man O’War

There’s been a pub on this hilltop spot in north county Dublin since at least 1595. The unusual name of the Man O’War, though, has nothing to do with battles but is a translation from the Irish mean bharr, or ‘middle height’ due to its elevated location on the old road between Dublin and Belfast, where it served as a popular place to break up the journey. When a 1732 Act of Parliament established the Dublin to Dunleer Turnpike as a tolled coach road, the Man O'War Pub was an obvious choice as the appointed toll booth, or turnpike. A 29-year-old Dublin barrister, Theobald Wolfe Tone, breakfasted here in 1792, a year after he attended the inaugural meeting of the Society of the United Irishmen that would eventually result in the failed uprising of 1798.

The Hole in the Wall

Europe’s longest public house, with exactly 100 metres of pub hugging the exterior wall of the 1700-acre Phoenix Park, the Hole in the Wall started life in 1651 as a medieval coaching inn known as ‘Ye Signe of Ye Blackhorse.’ In the 19th century it was a popular spot with luminaries including Daniel O’Connell, while in the 1950s President Sean T O’Kelly was a regular. It earned its current name in the late 19th century for serving pints through a hole in the park wall to thirsty soldiers barracked in the park but forbidden from leaving its boundaries.

The Long Hall

The Long Hall is the jewel of Dublin’s glittering collection of Victorian pubs, but it was originally established in 1766, at the height of the Georgian era. Subsequent alterations resulted in the handcrafted mahogany bar with brass-trimmed counter, elaborate partitions with gold leaf detail and the ornate stained glass and beveled mirrors that you see today. It has even retained its original Victorian dispensers of port and brandy. Its name comes from the long and narrow snug that once ran behind the bar – complete with a separate entrance and serving hatch for women (so they didn’t interfere with the men-only main bar).

Even less well-known is the bar’s 19th-century role as a recruitment hub for the Irish Republican Brotherhood. The pub was infiltrated by spies from nearby Dublin Castle however, which led to the arrest of owner Joseph Cromien and the closure of the pub ahead of the abortive Fenian uprising of 1867. These days the clientele are far less controversial, and include Bruce Springsteen when he visits the city.

The Stag’s Head

Though there was a tavern on this premises since 1780, and even a popular music hall venue in the early 19th century, the Stag’s Head is best known for the wow-factor splendour of its Victorian-era redesign unveiled in 1894. Its then-owner was George Tyson, an entrepreneurial menswear and haberdashery merchant and ‘outfitter and shirtmaker to the Lord Lieutenant’ of Dublin. With a mission to attract the city’s finest heeled clientele, he commissioned leading architect A.J. McLoughlin to conceive a pub to out-dazzle every other in the city – quite literally. It was the first pub in the capital to be lit by electric light, refracted in gleaming mirrors and stained glass windows, polished wood panelling and the glinting eyes of its enormous stag’s head hanging above the bar.

Mulligans of Poolbeg Street

A popular spirit-grocers shop from 1782 and a shebeen (unlicensed drinking premises) before that, Mulligans got its name when John Mulligan took ownership of the premises in 1851 and turned it into a licensed premises a year later. The young James Joyce was a regular here, and he set the pivotal arm-wrestling scene of his Dubliners short story ‘Counterparts’ in the back room that now carries his name. In the 1950s, a young American journalist working for Hearst Newspapers came to pay his respects at Joyce’s favourite seat at the bar; less than a decade later, John F Kennedy had abandoned journalism and was elected president of the United States.

Johnnie Fox’s

High up in the mountainside village of Glencullen overlooking the city below, Johnnie Fox’s has been synonymous with traditional Irish culture since the 1950s, when it hosted a popular Sunday night programme of traditional music and storytelling, broadcast by RTÉ. A far cry from its origins in 1798, when it was a small holding farm operating as a safe haven for Irish fighters during the 1798 Rebellion against British rule. In subsequent decades it became a favourite watering hole for the ‘Liberator’ Daniel O’Connell, who lived locally and hosted some of his rousing meetings in the bar.

Kehoe’s

If you’re curious for a sense of what Ireland’s historic pub-grocers were like, simply step inside the front door of the wonderfully preserved Kehoe’s, which opened its doors just off Grafton Street in 1803. Imagine leaning across the low grocery counter to order tea, coffee, rice or whatever other provisions you needed from the (still-intact) mahogany drawers. Then you’d slip into the adjacent snug to enjoy a warming tipple in privacy while your order was being despatched, with a buzzer on hand should you fancy a second.

Beyond two mahogany doors with stained glass insets, the back bar was where you might spot Dublin’s literati in the 1940s and ‘50s – although the more boisterous among them like playwright Brendan Behan and poet Patrick Kavanagh regularly found themselves barred from this respectable public house.

Slattery’s

Though Slattery’s has been a licensed premises since 1821, it wasn’t until the 1890s that it was given permission to open at 7am so it could service early morning traders at the newly developed Dublin Corporation Markets on nearby Mary’s Lane. The pub became one of Dublin’s best-loved ‘early houses,’ where market workers, local traders and even inspectors enjoyed a tipple amid the ornate décor, which includes a distinctive Edwardian island-style bar. The upstairs Paddy’s Bar is named in honour of publican Paddy Slattery, who fostered Irish music sessions here for three decades; in the 1980s, Thin Lizzy drummer Brian Downey played here every week.

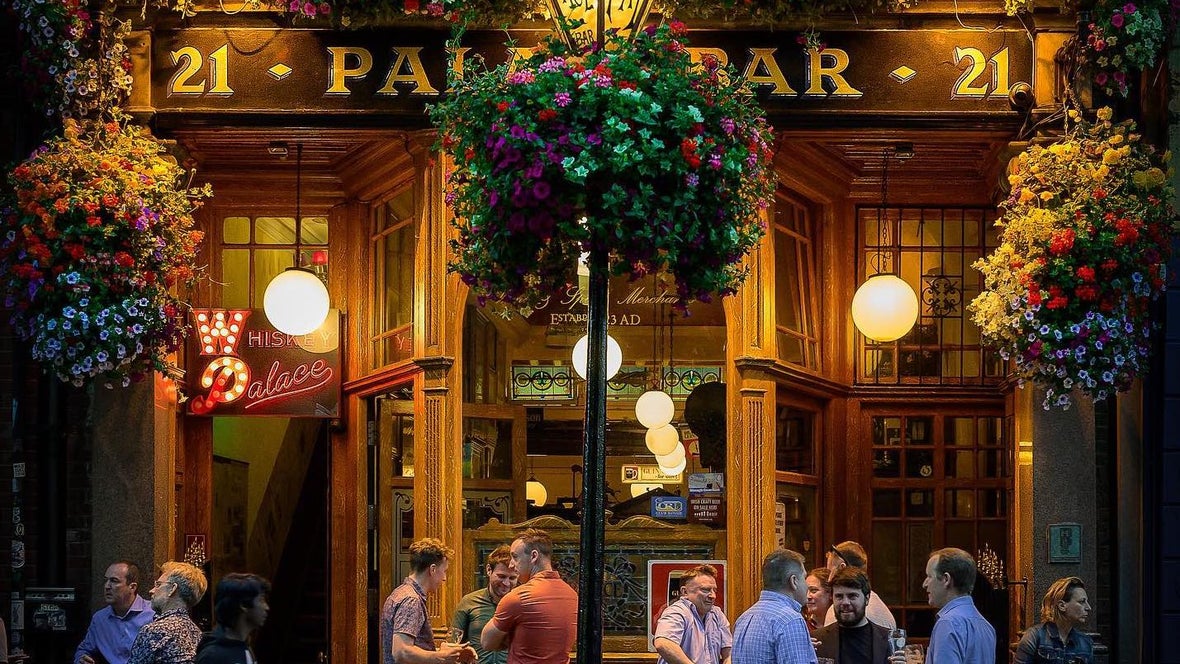

The Palace Bar

The Palace Bar on Fleet Street in Temple Bar celebrated its 200th birthday in 2023, but this Georgian beauty – later given a Victorian makeover – really came into its own in the 20th century, when it was the unofficial HQ of Dublin’s literary crowd. One of the best known regulars during the 1940s and 1950s was absurdist writer Flann O’Brien (real name Brian O’Nolan, who also wrote satirical newspaper columns under the name Myles na gCopaleen), who immortalised his love of the pub in ‘The Workman’s Friend,’ which includes the well-known refrain, ‘a pint of plain is yer only man.’ O’Nolan kept lively company at the Palace, alongside other writers including Patrick Kavanagh, Brendan Behan and poet Austin Clarke. The then-editor of The Irish Times, RM ‘Bertie’ Smylie, operated out of the back bar, which became notorious for its late-night lock-ins: one story tells of a police raid discovering O’Nolan hiding in the telephone box by the bar, and the writer protesting his innocence by saying that he wasn’t hiding but was waiting 45 minutes for a transatlantic connection.

Find a snug and get cosy

Comfort is one of the key ingredients of a great Dublin watering hole. Settle in with your drink of choice at one of the capital's cosiest pubs.